Christian-History.org does not receive any personally identifiable information from the search bar below.

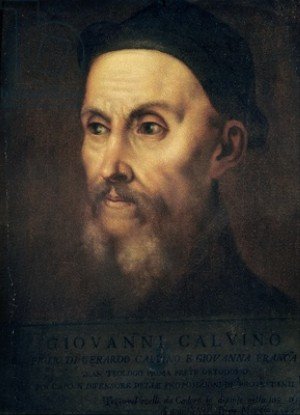

John Calvin, Swiss Reformer

I'm finishing this John Calvin page as I have time. I'm trying to do a good job, so I have spent at least 12 hours on it so far. I can read 50 pages an hour even in a history book, so I'm certain I've read over 300 pages in history books and web pages besides the writing and re-writing I've done.

Only his time in Geneva is left, and it's the only project I'm working on besides blogs till it's done. There's a LOT here already.

Don't miss the Cardinal Sadolet page, which has excerpts from Calvin's defense of the Reformation. It's the best explanation and defense I've ever heard, and I've heard many.

John Calvin was born July 10, 1509, about the time Martin Luther was learning the doctrine of salvation by faith alone in an Augustinian monastery in Germany. By the time he experienced what he described as conversion in 1530 or 1531, the Reformation was well-established in Germany, many of the German electors being already Protestant.

Ad:

Our books consistently maintain 4-star and better ratings despite the occasional 1- and 2-star ratings from people angry because we have no respect for sacred cows.

Even after his conversion, of which very little is known, Calvin did not officially leave the Roman Catholic Church. In 1533 he went to Paris to attend the College Royal. He was friends with Nicolas Cop, the rector, who was sympathetic to the Reformation, though the college itself was not.

The rector was scheduled to deliver an inaugural address on November 1, 1533, and he asked John Calvin to prepare it. Cop intended to call for reformation within the Roman Catholic Church. Calvin, through Nicolas Cop, declared that day:

[The Roman Catholic priests] teach nothing of faith, nothing of the love of God, nothing of the remission of sins, nothing of grace, nothing of justification; or if they do so, they pervert and undermine it all by their laws and sophistries. I beg you, who are here present, not to tolerate any longer these heresies and abuses. (Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. VII, ch. 74)

As you may imagine, that address was not well-received! The faculty was incensed. Cop fled immediately to Basel in Switzerland. John Calvin himself climbed out a window by tying sheets together, costumed himself as a vinedresser, then walked out of the city with a hoe on his shoulder. His room was searched, and all his papers were seized. He spent most of the next year in Angouleme, France, under the protection of Queen Marguerite of Navarre.

It is at this point that we can say that John Calvin was no longer Catholic. On May 4, 1534 he resigned all ecclesiastical favors granted him as a scholar. His stay in France had to come to an end, however, due to an event in which his role is unknown. It is possible he had nothing to do with it.

On the morning of October 19, 1534, the king of France awoke to find a poster on the door of the royal chamber at Fontainebleu, where he was staying. The poster called the mass a blasphemous denial of the one, all-sufficient sacrifice of Christ and referred to the pope and "all his vermin" as servants of the antichrist.

Similar posters were put up all over Paris, and, quite naturally, persecution arose immediately. No one knows whether John Calvin played any part in this, but he decided it would be a good time to leave France, going to Basel to be with Nicolas Cop in January of 1535.

In Basel he published his first edition of Institutes of the Christian Religion, his opus magnum, and one of the most influential works in Christian history. This first edition came out in March of 1536, though it was edited and expanded many times during Calvin's life.

Calvin is known most for his work in Geneva, which began later in 1536, but we should delay that story to discuss Institutes.

The Institutes of the Christian Religion

The publication of John Calvin's Institutes brought immediate praise among the reformers. Martin Bucer, one of the most respected of the Swiss reformers, wrote:

It is evident that the Lord has elected you as his organ for the bestowment of the richest fullness of blessing to his church. (Schaff, ibid., ch. 79)

The Roman Catholics had an equally strong but opposite reaction. They called it "the Koran and Talmud of heresy," and it was ordered burned throughout France and Switzerland.

To this day, it is one of the most respected Christian writing among Protestants, and it is revered by those churches that still call themselves Reformed. Dr. Karl von Hase, a German theologian of the 19th century, called it "the grandest scientific justification of Augustinianism, full of religious depth with inexorable consistency of thought" (Kirschengeschichte, as quoted and translated by Schaff, ibid., ch. 79).

It would be hard to overstate the influence of John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion. Martin Bucer was 18 years older, was something of a guide and mentor to Calvin, and had been involved with both Luther, the German Reformer, and Zwingli, the Swiss Reformer.

Nonetheless, it is John Calvin, who first published Institutes a decade after Luther had already overthrown the pope's authority in Germany, who is remembered as the 3rd great Reformer, along with Luther and Zwingli. In fact, his name is more attached to the Reformation than any man except Martin Luther, despite the fact that he did not come along until it was in full swing.

John Calvin's Theology

TULIP and Predestination

John Calvin's theology runs much deeper than the 5 tenets of Calvinism. Institutes is published today in up to four volumes and runs around 1500 pages long in its English translation; however, the 5 tenets of Calvinism are by far his most well-known, and thus most controversial, teaching.

While the acronym TULIP was not invented by John Calvin himself, I think most would agree that Calvin's thoughts on predestination certainly include the tenets of TULIP whether or not it is fair to say they are "summed up" by them.

The letters represent these teachings:

Some Comments on TULIP

I really can't print the tenets of TULIP and act like there's anything Biblical about them. The idea that anyone can read the Bible or know anything about church history and believe TULIP is incomprehensible to me. I don't get it. It would be easiest to assume that Calvinists must not read the Bible, but I know from experience it isn't true. Some Calvinists, and even some great and godly men like George Whitefield and Charles Spurgeon, have devoted their lives to Bible study and still believe these clearly unscriptural ideas about God.

Yes, there are verses that could be interpreted in such a way as to defend TULIP. However, if you are to believe TULIP, there's not a page in the Bible that wouldn't be rendered nonsense at some point on the page.

Like I said, I'm simply astounded that anyone could both read the the Bible and believe these things.

David Servant of Shepherd Serve has done a reasonably brief and easily-read refutation of Calvinism's five points. He does an excellent job of bringing out the real problem with these doctrines, in that they are nonsensical, anti-Scriptural, and insulting to God.

Sorry, apparently I'm not very good at beating around the bush. I believe from experience with Calvinists that Calvinist doctrines promote arrogance and intellectualism, and from Scripture that they present a picture of God that is inaccurate and far from appealing.

Total Depravity

This is the teaching that man is "totally" depraved. This means that we are so depraved that we cannot even choose to believe in Christ. We can believe only if God gives us grace to believe.

Unconditional Election

God chooses those he will saved based on no reason whatsoever except his sovereign choice. There is no value in us or our deeds that influence that choice.

Limited Atonement

Jesus only died for the elect. He did not die for the lost.

Irresistible Grace

If God chooses you, you will respond. No one resists God's grace. Those who are chosen will be saved.

Perseverance of the Saints

If God chooses you to be saved, obviously you will continue to the end. Those who do not continue to the end of their lives only looked like they had grace, they didn't really have it.

Basically, John Calvin took the idea of justification apart from works and made it justification apart even from the will. He took God's choice to the extreme, and he removed all choice of man. This is not a real surprise. Martin Luther had already gone this route with his book The Bondage of the Will. It was an idea that he picked up from Augustine of Hippo, the great 4th century bishop.

Augustine teaches doctrines very similar to TULIP in his work A Treatise on the Predestination of the Saints. In fact, his teaching is similar enough that had he not preceded John Calvin, he could be called a Calvinist. However, he had not always believed these doctrines!

I was in a similar error, thinking that faith with which we believe in God is not God's gift, but that it is in us from ourselves. I thought that by it we obtain the gifts of God so that we may live temperately, righteously, and godly in this world. For I did not think that faith was preceded by God's grace … that we should consent when the Gospel was preached to us I thought was our own doing. (Augustine of Hippo, A Treatise on the Predestination of the Saints, book I, chapter 7)

Before Augustine—and then only in his later years, when we was bishop of Hippo—the hopeless condemnation of the lost, with no opportunity for salvation because they are not elect, cannot be found.

It is entirely possible that this doctrine of Augustine's was a reaction to the heretic Pelagius, who taught that man could be saved by his own free will, choosing to live holy and in obedience to God apart from God's grace. Augustine opposed him first with the historical teaching of the Church, that all men are called by God through the Gospel to a salvation wrought and empowered by the Spirit of God. Later, thinking through the issue of free will and grace, he used Scripture to convince himself, contrary to the historical teaching of the church, that the lost had no opportunity to be saved because they were not chosen!

Faith, then, as well in its beginning as in its completion, is God's gift; and let no one have any doubt whatever, unless he desires to resist the plainest sacred writings, that this gift is given to some, while to some it is not given. But why it is not given to all ought not to disturb the believer, who believes that from one all have gone into a condemnation, which undoubtedly is most righteous. (ibid. ch. 16)

Augustine, then, came to these things in response to Pelagianism. These doctrines then sat untouched until Martin Luther revived them and passed them on to John Calvin, who passed them on to the world.

The only reason I can find that Augustine might suggest that "the plainest sacred writings" teach that the gift of faith is given only to some is because of Romans 9. Admittedly, at first glance, especially if you have previously been accosted with Calvinism, Romans 9 is shocking. God would create some people as vessels of wrath, doomed to destruction???

Paul's answer in Romans 9 is yes, he would, and we are not to question him.

Calvinism, however, leaps to the conclusion that if God chose pharaoh to be condemned and chose Jacob over Esau, then God is in the business of randomly choosing who will be saved. The problem with this is that Paul has been telling us throughout the book of Romans who are these chosen and rejected ones that he is speaking of.

Romans 9 is part of the argument that God has rejected the Jews in order to admit the Gentiles to his covenant. Nor has he permanently rejected the Jews. He is provoking them to jealousy so that they, too, can be saved. What was the end of this long argument by Paul?

God has included them all [i.e., Jews and Gentiles both] in unbelief so that he might have mercy upon all. (Rom. 11:32)

This is the God known by Bible believers, the one who "wills that all men should be saved and come to a knowledge of the truth" (1 Tim. 2:4).

Geneva, Switzerland; 1536 to 1538

I promised to return to John Calvin's story. Besides the theology that he promulgated through The Institutes of the Christian Religion, it is his rule in Geneva, Switzerland that is most remembered. It is a detailed story, and I am afraid we will have to limit ourselves to the highlights.

Calvin was simply passing through Geneva in July of 1536, intending to stay only a night. William Farel, however, who had been working tirelessly—and effectively—to bring the Reformation to Geneva, had other ideas. On May 21, he had gotten the city council to publicly introduce the Reformation. Now, he pleaded with John Calvin to help him give it birth.

Did I say pleaded? That word is too weak! When cajoling and pleading did not work, he threatened Calvin with the wrath of Almighty God if he "preferred his studies to the work of the Lord, and his own interest to the cause of Christ" (Schaff, ibid., sec. 81).

So Calvin stayed. He and Farel set about cleaning up Geneva. Like most cities that require its citizens to be "Christians," very few of Geneva's citizens actually lived like Christians. Prostitution was actually sanctioned by the council, and vice abounded. The priests, as was typical of medieval Catholicism, had neglected to teach the citizens anything of Christ, the Scriptures, or obedience to the faith.

John Calvin, Farel, and a reformer named Courald set about to rectify this. They wrote up a confession of faith, developed a catechism to instruct the people, preached five times on Sunday and several times throughout the week, and asked the council to pass laws forbidding immoral habits and gambling and requiring church attendance.

These things the council did, but the reformers had asked them as well to grant the right of excommunication to the spiritual leaders of the city.

Because the Roman Catholics had abused this power, the reformers asked that trusted citizens be appointed to oversee the matters of admonishment and church discipline. But because the Roman Catholics had abused this power, neither the council nor the citizenry was willing to grant this right to the Protestants, either.

When the council required all citizens to publicly affirm the confession drawn up by the reformers, the people began to stir. The council was maintained by elections, and on Feb. 3, 1538 an "anti-clerical" party managed to win a majority of council seats.

At the time the nearby city of Bern had also gone reformed, but they were not near so radical. Before Calvin had ever arrived, Farel had gotten the council to ban all holidays but Sunday, and citizens were punished if they were found with any relics of popery, such as a rosary.

Guillame "William" Farel

Guillame "William" FarelThe new council decided to pattern itself after Bern. They still set a curfew for the city, and they banned lewd songs in the streets, but they removed the requirement to swear to the new confession.

It wasn't sufficient for the reformers. They preached vehemently against the vices of the people, and they publicly condemned the council for not taking a stronger stand. Courauld, in fact, was so bold and so offensive in his speech that he was first forbidden to preach, then imprisoned, then banished, despite the protests of both Farel and John Calvin.

This did not frighten or even slow down Farel or Calvin. They spoke up all the louder. Calvin dared to call the council the devil's council. The people began to threaten them, even pounding on their doors at night.

John Calvin wasn't moved. When he and Farel were ordered to celebrate communion at Easter with unleavened bread the way the church in Bern did, they refused to grant communion, claiming rampant debauchery and insubordination. Swords were drawn and the reformers were shouted down when they announced this in the service, and within two days the council had deposed and banished them.

Calvin rejoiced at the persecution, and the people rejoiced publicly over their new freedom. Communion was administered the following week by new pastors.

Strassburg; 1538 to 1541

John Calvin's Liturgy

It is interesting to note that John Calvin developed a liturgy while in Strassburg. Luther had one as well. It must have seemed mandatory to the reformers. Meeting without one was something they had never known.

In Calvin's liturgy, the service started by calling on God, a group confession of sin (a general admission of sin to God, not a personal confession to a priest), and an absolution. They then chanted Psalms together before the pastor preached a sermon, offered a long, free prayer, and then prayed the Lord's prayer with the congregation. Singing and a blessing then ended the service.

Communion was once per month in John Calvin's congregation in Strassburg. Baptisms, when necessary, were done after the service. Calvin believed that immersion was the original apostolic practice, but he also believed that sprinkling or pouring were acceptable.

William Farel was immediately beckoned to Neuchatel, where he had worked before. It was several months before Martin Bucer, lead reformer in the city of Strassburg, sent for John Calvin to join in the work there.

Strassburg is a beautiful, fortressed city, a part of Germany then and France today. With the peaceable Martin Bucer leading it, it had proven to be a bridge between Lutheranism and Zwinglianism, at that time the only two branches of the Reformation, one German and one Swiss. It was only later that John Calvin's leadership in Geneva and his Institutes would lead to a third branch.

John Calvin arrived in Strassburg in September, 1538. It would prove to be preparation for the rest of his life. Bucer taught him some tolerance and graciousness, at least until he was in full control of Geneva, and he got to know the Lutherans, gaining an appreciation for them, and possibly a knowledge of predestination which would come to be known as Calvinism. The original confession of Geneva, drawn up by John Calvin and William Farel, had contained no mention of predestination.

It is mentioned by the historian Philip Schaff that Calvin had the freedom to enforce the church discipline that he had been unable to enforce at Geneva. Discipline was as important to him, he says, as doctrine was to Luther (ibid., sec. 86).

The discipline may have been strong, involving excommunication, but it was not strict. The first person who was banned from the communion table had avoided church meetings for a month and fallen into gross immorality. This is hardly a harsh requirement! No wonder John Calvin insisted on it. Surely anyone wanting to build a church is going to want to keep the openly immoral from the communion table!

Calvin built up a large church there in Strassburg, preaching four times weekly, including twice on Sundays. He converted many anabaptists, and he was well-respected by his congregation. Interestingly enough, when he returned it 1556 he was greeted warmly but forbidden to preach, as the congregation had become thoroughly Lutheran. Because Calvin did not preach "consubstantiation," the doctrine that Christ's actual body and blood is in some way in the bread and wine of communion, his teaching was no longer welcome.

While in Strassburg, he released the second edition of Institutes, and he also wrote a commentary on Romans. He would become one of the most prolific Reformation authors, though no one could match the tireless pen of Martin Luther.

Roman Catholicism and Justification by Faith

John Calvin attended a diet (a gathering of princes) at Regensburg in April, 1541. It was called by the emperor Charles V. His hope was to gather clerics of the Lutherans and Catholics in order to produce a reconciliation that he felt he needed in order to rouse a proper army against the invading Turks.

Obviously, the diet of Regensburg failed to reunite the Catholics and Protestants, but it is important to take note of the differences.

It is commonly thought that the Protestants and Catholics divided over the issue of justification by faith alone. This is not true. Martin Luther learned of justification by faith in an Augustinian monastery from Johann von Staupitz, a Catholic priest. While such a Gospel was not generally taught in the Catholic Church, it was not heresy.

Nor was predestination! The reformers had "Saint" Augustine to rely on to back them up on that subject.

Instead, the diet remained divided over two issues, the power of the church and transsubstantiation, the doctrine that the bread and wine of communion became, literally, the meat and blood of Christ. These were also the issues that Protestants faced martyrdom over.

John Calvin's Marriage

John Calvin married Idelette de Bure in August of 1540. He was 31 at the time, and the story surrounding his marriage is quite interesting.

Calvin delayed marriage partly to prevent the Roman Catholic Church from accusing him of leaving them in order to get a woman. Later, when he did decide to marry—at the urging of friends who felt he needed help at home—he stated that he would not choose a wife based on earthly beauty. In a letter to Farel from 1539, he described the attributes of the woman of his dreams: "chaste, obliging, not fastidious, economical, patient, careful for my health."

Apparently his friends were trying to seek out a wife for him, but when Farel read these qualifications, he gave up. He knew of no such woman.

In February of 1540 he mentions that a noble woman had proposed to him, quite rich, but he could not go through with it because she did not speak his language (!) and he was worried she would be too concerned with family and education. Philip Schaff suggests that the proposal was probably made through Martin Bucer because the woman was from Strassburg, thus a German speaker. Calvin spoke French and Latin (and learned Greek and Hebrew as well for Bible study).

In March of 1540, he had his brother send a woman who had agreed to marry him. That fell through for unknown reasons.

Finally, he married a woman of his own congregation, a widow of a man that he hand converted from anabaptism. Schaff states that she had "several children." Others suggest that she had two children. Wikipedia cites two recent biographies, by Bernard Cottret and T.H.L. Parker, for that information.

Researching Calvin

It was surprisingly difficult to find information on Calvin's children. I do not tell you that to complain but to let you know what you are getting at this web site.

Who knows what you can trust on the internet? I am not a professional historian, but insofar as possible I have avoided all hearsay on this site. The effort that went into finding out whether John Calvin had three children or one by Idolette de Bure has been put into every difficult question on this whole site.

I give you sources on this site. I tell you why I'm telling you what I'm telling you. I have put somewhat less effort into those details of history that are not controversial, assuming that where all are agreed less effort is necessary. Where people are not agreed, I have put in many hours.

This page was not created in a day. I already knew John Calvin's story in general. However, I read over a hundred pages from Philip Schaff's History of the Church to prepare for this page. Schaff's history has the great benefit of being full of quotes so that it's possible to touch the spirit of the great Reformer.

I detest most of Calvin's doctrines, but his spirit in his early years is brave and full of care for Christ and for people. It makes it very hard to condemn him for what I consider to be great doctrinal errors. On the other hand, those errors were shared by Augustine, an equally great man who maintained a life of purity and poverty in the midst of an age of luxury and excess.

A man is always better judged by his behavior than by his belief because his behavior tells you what his real belief is.

I apologize for boasting of the research that went into this page; however, since this is the internet, where any fool can have a voice, I want you to know what a rich resource you have in this web site. I could easily have skipped any mention of Calvin's children. Many web sites do. After all, very little is known of them. It is hard, however—in fact, almost impossible—for me not to be thorough. I greatly fear misleading you or giving you something less than utterly trustworthy.

Calvin spoke very little of his home life, unlike Martin Luther, so after much research it appears to me that no one knows the gender of the children that Idelette de Bure brought to their marriage. In fact, there is question as to how many children John Calvin and Idelette had after their marriage. Certainly he had an infant son that died in 1542. Some biographies, however, suggest that he had three children. The other two, they say, were daughters who also died in infancy.

Schaff says this is a mistake. Dr. Jules Bonnet published a collection of letters by John Calvin, and included is a letter to Viret, the Genevan reformer, commenting on the death of an infant daughter. Schaff says this is impossible because in Responsio ad Balduini Convitia, written in 1561, Calvin mentions that God had given him a little son, then taken him away. There is no mention of any other children. Further, Nicolas Colladon, a friend of John Calvin's later in Geneva, wrote in his biography that Idolette had but one son from John Calvin.

John Calvin Returns to Geneva

A great precursor to the story of John Calvin's return to Geneva is his controversy with Cardinal Sadolet. Each side wrote only one letter, but even the excerpts from Calvin's letter are so powerful that they comprise the best defense of the Protestant Reformation that I have ever seen.

Things had not gone well after Calvin had been banished from Geneva, which is something he had predicted. It took only a year for his opponents to split into factions. The people, happy to throw off the yoke of both Christ and the reformers, degraded into rampant immorality. It was so bad that historian Philip Schaff reports, "Persons went naked through the streets to the sound of drums and fifes" (ibid., sec. 93).

The council began to think they had made a mistake, and in 1540 they began to court Calvin, asking him to return.

This turned out to be a huge issue, and everyone had opinions. Martin Bucer in Basel spoke up, at various points taking both sides. William Farel assailed Calvin without retreat, calling for his return to Geneva, and even warned him to remember Jonah. Philip Melancthon, Martin Luther's sidekick, had become friends with Calvin in Germany and was heartsick at the thought of his return to Switzerland.

The issue was the importance of the cities. Both were crossroads, sitting near the border of France, Switzerland and Germany. Strassburg spoke German; Geneva spoke French. The former was seen as more crucial to the Reformation, the latter was thought to provide hope for the spread of the Reformation to France, where it had been cruelly put down.

Needless to say, after much debate and negotiotian, John Calvin returned to Geneva. The one point he steadfastly required is that church discipline be allowed.

Church Discipline in John Calvin's Day

Church discipline was a big issue to Calvin. Obviously, church discipline under the Roman Catholic Church had been out of control. Delivered from the unrestrained power of Catholic bishops and the local governments under their control, the citizens—especially the more rich and influential—wanted to take all power from the reformed churches.

Calvin thought this was impossible, and it had been an issue during his first stay in Geneva. He was not asking for anything that was not obviously Scriptural. He wanted the right for pastors to privately admonish the members of their congregation, to denounce open sin openly, and to finally excommunicate the unrepentant.

In the early church this was strong discipline, but nothing like it was in the 16th century. In the first couple centuries after Christ, you lost only the fellowship of the church. After the 4th century, everyone was "Christian." Excommunication immediately ruined your life, ending all your business transactions and forcing even your immediate family—who would also all be "Christian"—to cease interaction with you.

Note that "excommunication" means to ban from communion. It does not in and of itself mean banishment from all communication, though in practice this is often what resulted.

Calvin writes:

Though ecclesiastical discipline does not permit us to live familiarly or have intimate contact with excommunicated persons, we ought nevertheless to strive by whatever means we can in order that they may turn to a more virtuous life and may return to the society and unity of the church. (Institutes, Bk 4, ch. 12, sec. 10)

John Calvin did not want to take over the work in Geneva alone. He tried to secure the services of William Farel or Peter Viret. Both were needed elsewhere, however, Farel in in Neuchatel and Viret in Lausanne.

Pierre "Peter" Viret

Pierre "Peter" ViretJust as a matter of interest, these 3 Swiss Reformers, of whom only Peter (actually, Pierre) Viret was actually Swiss, were among the most noted in their day. Theodore Beza, who would become Calvin's successor at Geneva, said of them that Calvin was the most learned of the Reformers, Farel the most forceful, and Viret the most gentle.

John Calvin was only 32 when he returned to Geneva. He had Farel to turn to on a regular basis, but otherwise the work was completely his. It was not minor:

He had to reorganize the Church, to introduce a constitution and order of worship, to preach, to teach, to settle controversies, to conciliate contending parties, to provide for the instruction of youth, to give advice even in purely secular affairs. (ibid., sec. 96)

It would be a rocky road. Imagine trying to run a church that everyone was required to be in. It was unavoidable that he would make many enemies, especially with the kind of discipline that he was trying to maintain in Geneva. The next 23 years would be filled with trials and battles, more within Geneva than even outside of it.

Peter Viret was with him at the beginning. Geneva had managed to secure him at the end of 1540, a few months before Calvin returned. He stayed with Calvin for a year before he had to return to Lausanne. This was of inestimable comfort to Calvin.

A sunset in Alabama

A sunset in AlabamaBut Calvin was wise enough not to do it alone. Viret had written him in Strassburg telling him that if he did not come, then Viret would have to perish or leave. The work, he said, was utterly overwhelming.

The only way it could be different for John Calvin was for him to administrate better, and he did. First he secured the cooperation of the councils of Geneva. He went to the councils with an "ecclesiastical order," which was basically a charter for the church. His willingness to compromise secured the acceptance of the ordinances, and they were approved by all 3 of Geneva's councils and the people.

His humility through all this was extraordinary. He avoided, purposely, taking vengeance on his defeated enemies or even denouncing them from the pulpit:

On my arrival it was in my power to have disconcerted our enemies most triumphantly, entering with full sail among the whole of that tribe who had done the mischief. I have abstained; if I had liked, I could daily, not merely with impunity, but with the approval of very many, have used sharp reproof. I forbear; even with the most scrupulous care do I avoid everything of the kind, lest even by some slight word I should appear to persecute any individual, much less all of them at once. May the Lord confirm me in this disposition of mind. (ibid., sec. 96)

What a great attitude!

Thus securing the cooperation of government and people, he went to work on getting help for his labors. By 1544, just three years after he arrived, he had a dozen pastors. He also trained a number of evangelists.

The work in Geneva had begun in earnest.

John Calvin's Work in Geneva Doesn't Begin Well

So what is this that was spreading to Italy and influencing France from John Calvin. What benefit was John Calvin's presence providing?

There was a lot of focus on doctrine during the Protestant Reformation, and it has carried over to us modern Protestants. What John Calvin emphasized most of all, though, is talked about in his letter to Cardinal Sadolet.

Among the people themselves, the highest veneration paid to Thy Word was to revere it at a distance, as a thing inaccessible, and abstain from all investigation of it. Owing to this supine state of the pastors, and this stupidity of the people, every place was filled with pernicious errors, falsehoods, and superstition.

John Calvin wanted the people to know the Scriptures. He wanted them to stop worshiping saints and start worshiping Christ. He wanted them to "duly consider … that one sacrifice which [Christ] offered on the cross." He "dwel[t] at greater length on topics on which the salvation of [his] hearers depended." Above all, he said he knew that "this is eternal life to know Thee the only true God, and Jesus Christ, whom Thou hast sent."

Whether we like John Calvin's specific doctrines or not (and I don't), he is to be commended for turning people to the Scriptures, calling them away from the worship of saints, and teaching them to know Christ for a "sure and unfaltering hope of salvation."

This page is going to be too long, but this is a great story!

John Calvin had a lot of trouble with those pastors he put to work in Geneva … a lot of trouble.

I'll let him describe it:

I labor here and do my utmost, but succeed indifferently [i.e., so-so, not much to take heart about]. Nevertheless, all are astonished that my progress is so great in the midst of so many impediments, the greater part of which arise from the ministers themselves. (ibid., sec. 96)

That was from a letter to Melancthon in February, 1543. That was almost two years after his return. Before that, he complained even more about these pastors. In a letter to Basel begging to keep Peter Viret for a while, written in March, 1542, he says:

Our other colleagues are rather a hindrance than a help to us; they are rude and self-conceited, have no zeal and less learning. But what is worst of all, I cannot trust them, even although I very much wish I could; for by many evidences they show their estrangement from us, and give scarcely any indication of a sincere and trustworthy disposition.

Ouch!

It wasn't all bad. He adds in the letter to Melancthon:

This, however, is a great alleviation of my troubles, that not only this Church, but also the whole neighborhood, derive some benefit from my presence. Besides that, somewhat overflows from hence upon France, and even spreads as far as Italy.

Overview of John Calvin's Time in Geneva

Late in 1541, he was asked to help draft a new set of laws along with the four "syndics," who were the highest leaders in Geneva and members of both the larger and smaller councils. These laws concerned everything down to the roles of firemen and watchmen on the wall. Later, in the 1560's, these would be revised again by John Calvin's friend, Germain Colladon.

Despite his influence with the councils, John Calvin never held political office. And while he was consulted on major decisions, he did not regularly appear before the council. He has been called the pope of Geneva, but it would not be accurate to call him the civil head of Geneva.

His greatest influence was theological. He debated heretics in print, wrote letters of advice to many from around Europe who consulted him, and preached almost daily. Visitors flocked from Germany, France, Italy, and Spain to hear him, and eventually there was even a Spanish-speaking congregation in Geneva.

Farel and Viret continued to appear in Geneva from time to time, and together they became the most influential teachers of their time with the exception of Philip Melancthon in Germany.

There was a tie between state and church in John Calvin's Geneva. Calvin taught, and the government agreed, that they were to "cherish and support the external worship of God, the true doctrine of religion, to defend the constitution of the church … " (Schaff, vol. VIII, ch. 13, sec. 101). There was really nothing unusual about this. Freedom of religion would have to wait at least two centuries to be found anywhere in the world.

In a state with no freedom of religion, there will be no freedom of press, either. Geneva's press law forbad "popish, heretical, and infidel publications" (ibid.).

On the other hand, their press law called for privileged initial publication of new translations of the Scripture. As a result, it was in Geneva in 1551 that Robert Stephen, after being censored in Paris, published the first New Testament containing verse divisions as we have them today.

The "Geneva Bible" was also published there in 1560, and it was the primary English translation in Europe for more than 50 years until being displaced by the King James Bible in the early 1600's.

The Execution of Michael Servetus

John Calvin has been much maligned for his role in the execution of the heretic Michael Servetus. Servetus had a lot of theological opinions, and it appears that he longed his whole life long to be engaged in debate and discussion with the leading Reformers. Calvin knew of him back in Paris, while both were being searched for by the Spanish Inquisition, and wrote that he visited Servetus to try to convert him.

Around 1535, though, Servetus put out a book called De Trinitas Erroribas Libri Septum (On the Errors of the Trinity). In it, he denied the pre-existence of Christ and aroused the wrath of Roman Catholics and Protestants alike. Ephraim Emerton, in a Harvard Theological Review article in 1909 wrote:

Bucer in Strassburg, often known as the peacemaker of the Reformation, seems at first to have listened with some patience [to Servetus], if not actual interest, to the Spaniard's vagaries, but now, having read his book, he publicly declares that such a man ought to be disembowelled and torn to pieces. ("Calvin and Servetus," p. 149)With everyone after him, Servetus fled to France for almost 20 years and changed his last name to Villeneuve.

In the 1550s he emerged again, writing to major Protestant leaders under his new name. Despite managing to avoid the connection with his book, he was declared a heretic again and arrested by the Roman Catholics. He managed to escape, and went to Geneva to talk to John Calvin.

He was arrested as soon as he arrived, though Calvin did agree to debate him in hopes of converting him. Servetus, though, or Villeneuve as he was calling himself, did not bend in the least. In fact, he was haughty and insulting, assuring not only his condemnation but his death.

Calvin was consenting to his death. He did try to get the Genevan council to find a less cruel form of execution than burning at the stake. We must remember that since the time of Augustine in the fifth century, the use of the sword for conversion and for the execution of heretics was justified by almost all. They were a threat to society and especially Christian society.

"Christendom" is a word that is used of Christianity when united with the state, with the secular power. Ever since the churches of the Roman Empire allowed Emperor Constantine into their affairs, violence and execution have followed. Emerton's article ends with a chilling description of this:

The spirit of persecution has never lacked arguments, and never will, whenever the fatal union of civil and religious power puts effective weapons in its hands. (ibid., p. 160)If we are to condemn John Calvin for arguing for the "spirit of persecution," then we must condemn Augustine, Thomas Aquinas, all the Reformers, and all who lie between them in time. If the condemnation confined to the fact that anyone who has read Jesus or the apostles must know that Jesus would never approve of persecution, execution, or murder by Christians, whether they executed by their own power or used the state as their weapon, then the condemnation is certainly justified, but it cannot be limited to John Calvin and Servetus.

Along with Ephraim Emerton's article, I am indebted to the Christian History Institute for an excellent and concise article titled "The Servetus Affair."

This is an ad written by me, Paul Pavao: I get a commission if you buy Xero shoes, which does not increase your cost. Barefoot running/walking is the best thing for your feet--if we did not walk on cement, asphalt, and gravel. Normal shoes compress your toes and do a lot of the work your lower leg muscles should be doing. Xero shoes are minimalist and let your toes spread and your feet do the work they are supposed to do. More info at the link.

Early Church History Newsletter

You will be notified of new articles, and I send teachings based on the pre-Nicene fathers intermittently.

When you sign up for my newsletter, your email address will not be shared. We will only use it to send you the newsletter.