Christian-History.org does not receive any personally identifiable information from the search bar below.

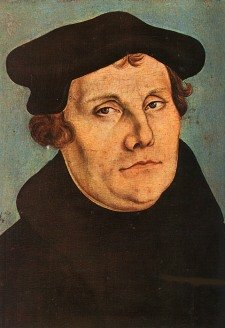

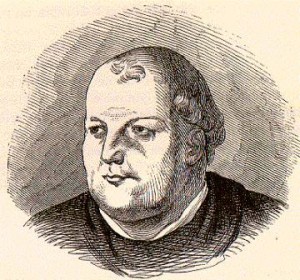

Martin Luther

Martin Luther was born November 10, 1483 at Eisbleben in Prussian Saxony, and he died on February 18, 1546. In between, he changed the world, laying the foundation for free democracies.

Luther, a simple German monk of peasant background, had as much influence in shaping our modern world as almost anyone who has ever lived. He was a puzzling, determined man of extraordinary conviction, determination, and boldness. Few people in history have produced as many interesting stories—positive and negative—as Martin Luther.

Ad:

Our books consistently maintain 4-star and better ratings despite the occasional 1- and 2-star ratings from people angry because we have no respect for sacred cows.

Major Events of Luther's Life

There are several notable events that should be covered in order to know what Martin Luther did. Further down the page, we will cover events that will help us know who Martin Luther was.

1517: The 95 Theses

Martin Luther came to the forefront of history by nailing 95 theses to the cathedral door at Wittenberg. This was a typical method of requesting public discussion of an issue, but this was no ordinary issue. Luther, the unknown Augustinian monk, was taking on the Roman Catholic Church on the matter of indulgences, Rome's primary method of fundraising for Pope Leo X's pet project, St. Peter's Basilica.

This protest against indulgences would become a protest against Rome itself and thus marked the start of the Protestant Reformation.

Amazingly, this protest would succeed, gain the support of German nobles, and overthrow the dominion of the pope in central Europe. In fact, no public discussion took place at all, but students—who already agreed with him—published and spread the 95 theses throughout Germany in the matter of a few weeks.

Keep in mind though, that at the time …

Luther had as yet no idea of reforming the Catholic church, and still less of separating from it. All the roots of his life and piety were in the historic church, and he considered himself a good Catholic even in 1517, and was so in fact. He still devoutly prayed to the Virgin Mary from the pulpit; he did not doubt the intercession of saints in heaven for the sinners on earth; he celebrated mass with full belief in the repetition of the sacrifice on the cross and the miracle of transubstantiation. (History of the Christian Church, Vol. VII, ch. 2, sec. 29)

Later, shortly before his death, Luther would write a preface to the 95 theses describing himself as an "insane papist" at the time, and he added, "I would have readily murdered any person who denied obedience to the Pope."

1518: Martin Luther Takes on Pope Leo X

Though Pope Leo X tried to ignore the controversy at first, it took him only 3 months to realize he had to do something. He appointed a commission of inquiry under Dominican scholar Silvester Mazzolini, a professor of theology.

Professor Mazzolini did not know what he was getting into.

He wrote a dialogue in Latin against Luther's theses (which had also been published in Latin), but Luther simply dismissed it. He republished it with an introduction that called it haughty, Italian, and typical of the school of Thomas Aquinas.

So Mazzolini wrote another. Again Luther republished it, and he advised Mazzolini not to make himself any more ridiculous by continuing to write.

All tolerance left the pope at that point. Martin was called to Rome to recant his heresies. Leo X also demanded of Frederick the Wise, Elector in charge of Wittenberg where Luther was professor, that he deliver up this "child of the devil."

Frederick the Wise, however, was quite impressed with Martin Luther, so he took up Luther's cause and arranged an interview with a papal representative at the diet [formal general assembly of princes] in Augsburg. He also obtained a promise of kind treatment and safety.

1518 portrait of Pope Leo X

1518 portrait of Pope Leo XThe interview didn't go well. The papal legate was Cardinal Cajetan, and when he asked Luther to recant, Luther told him he wanted to speak to Pope Leo X. He explained to Cardinal Cajetan that if Peter was rebuked by Paul and was thus not infallible, then surely Peter's successor was not infallible, either.

Cajetan was furious. He told Luther never to enter his presence again unless he revoked his views. He urged Luther's superior to work to convert him, and called Luther a "deep-eyed German beast with strange speculations."

Luther was forced to flee by night from Augsburg. He got back to Wittenberg on the anniversary of the 95 theses, October 31. He again appealed to speak to the pope, then quickly gave that up and requested a general council.

Apparently, the stress was more than Martin Luther could handle. He expected to be excommunicated any day, which was a much greater punishment in his day than ours. All of society was Roman Catholic in 1518, and Luther's living came from teaching in the monastery, the cathedral, and the university. He would lose his job, and he would have no means of getting another or doing business, for no one would be allowed to do business with him.

He steeled himself for the battle and apparently turned wholeheartedly against Rome. He wrote:

The more those Romish grandees rage, and meditate the use of force, the less do I fear them, and shall feel all the more free to fight against the serpents of Rome. I am prepared for all, and await the judgment of God. (ibid., ch. 3, sec. 35)

1519: The Amazing Karl von Miltitz

For some reason, the pope decided to attempt some diplomacy before dealing harshly with Luther. He sent his chamberlain, Karl von Miltitz, of Saxon descent himself, to Elector Frederick the Wise with a gift and to talk with Martin Luther.

The interview with Luther went exceptionally well. Miltitz put much of the blame for the controversy on John Tetzel, the famous hawker of indulgences, and agreed to let a German bishop decide the matter.

This worked. Luther promised to ask for pardon from the pope and to plead with the people not to divide from the Church.

On March 3, he wrote a letter to the pope expressing great humility but refusing to back away from his convictions. Then he did indeed exhort the people not to separate from the Church in which so many martyrs had given their blood.

The Church of the Martyrs

If you object, as I do, to the idea that the Church in which so many martyrs gave their blood is the Roman Catholic Church, take heart. Martin Luther soon agrees with us.

The Church prior to and at the Council of Nicea was not Roman Catholic. By medieval times, when all of western Christendom (which was only Europe), was indeed Roman Catholic, they were spilling the blood of martyrs, not giving it.

Luther, as our story is about to show, found that out quickly.

1519: The Martin Luther – Johann Eck Debates

Martin Luther began his study of history around the time he wrote that letter to Pope Leo X. Only 10 days later, on March 13, he would write to Spalatin, Frederick the Wise's advisor:

I know not whether the Pope is anti-christ himself, or his apostle; so wretchedly is Christ, that is the truth, corrupted and crucified by him in the Decretals. (ibid., ch. 3, sec. 36)

The Pseudo-Isidorian Decretals were a collection of letters by "popes" from Clement I (c. A.D. 90) to Gregory the Great (c. 600). A decretal is nothing more than an official decision of the pope issued in written form. These letters were forgeries put together by someone calling himself Isidore Mercator around 842 in Metz. They were used by Rome to prove papal authority dating back to the most ancient times.

Martin Luther had obviously recently read the writings of Laurentius Valla, who had exposed the Isidorian Decretals as forgeries back in 1440, and he was incensed about the deceit. With the Decretals was the also-fictitious work, the Donation of Constantine, which purported to grant "Pope" Sylvester I secular authority over all of Europe.

So when Johann Eck proposed a disputation on the subject of papal primacy, as well as free will (which Luther denied), good works, purgatory, and indulgences, Luther jumped at the opportunity. It took place in July and lasted 3 weeks under the sanction of Duke George of Saxony included Luther's friend, Carlstadt.

Johann Eck

Johann Eckphoto by Dominik Hundhammer

Eck disposed of Carlstadt, an unskilled debater, in the first dispute on free will. He would not find Martin Luther so simple.

Luther is known for his sharp quill; his abuse of his opponents was harsh even for his era. In person, however, he was—for lack of a better description—charming and disarming. A German present at the debate described Luther this way:

His voice is clear and melodious. His learning, and his knowledge of Scripture are so extraordinary that he has nearly every thing at his fingers' ends. … A vast forest of thoughts and words is at his disposal. He is polite and clever. There is nothing stoical, nothing supercilious [i.e., arrogant or condescending], about him; and he understands how to adapt himself to different persons and times. … He is always fresh, cheerful, and at his ease, and has a pleasant countenance, however hard his enemies may threaten him, so that one cannot but believe that Heaven is with him in his great undertaking. Most people, however, reproach him with want of moderation in polemics, and with being rather imprudent and more cutting than befits a theologian and a reformer. (ibid., ch. 3, sec. 37)

To this day both sides claim to have won the debate. In the end, however, two important things happened. Luther gained even more followers; many students left Leipzig, where the debate was held, for the schools of Wittenberg.

Secondly, and even more importantly, the debate with Eck marked the complete separation of Luther from Catholicism. During the debate he had officially denied the infallibility of the pope and the general councils of the Church.

It is entirely possible that this was Eck's entire goal. Forcing Martin Luther to take a stand on Scripture—and notably, on early church history—against the authority of the pope and councils made Luther an official heretic and guaranteed his excommunication. It seems very unlikely that Eck or the pope could have foreseen the popularity of this deprived, insignificant monk.

1520: The Papal Bull Excommunicating Martin Luther

On June 15 or 16 of 1520, Pope Leo X officially excommunicated Martin Luther. He issued a papal bull expressly denying 41 topics from Luther's books, and it calls for all princes, magistrates, and citizens to seize Luther and his followers, turn them over to the pope, and burn all his writings. It gives Luther 60 days to repent and recant, and otherwise threatens him with being cut off from the church and punished as an obstinate heretic.

This obviously conveyed the threat of death by fire because the pope defends that practice in the bull.

However this time, rather than leading to the burning of Martin Luther's writings, and perhaps his person, the bull itself was burned publicly by Martin Luther.

The selection of Johann Eck to deliver the bull was a mistake. Eck and Catholic schools claimed victory at the debate at Leipzig, but Luther was extremely popular in Germany. Eck, Luther's enemy, was thus extremely unpopular by default.

When Eck tried to post the bull at Leipzig, he was accosted by 150 students from Wittenberg and had to flee to a convent. The bull was pulled down and torn to shreds.

In Erfurt, it was even worse. There even the theological faculty refused to publish the bull, and the students tore it up and threw in the water, referring to it by the Latin word bulla, which means bubble. "It is only a bubble," they said, "let it float on the water."

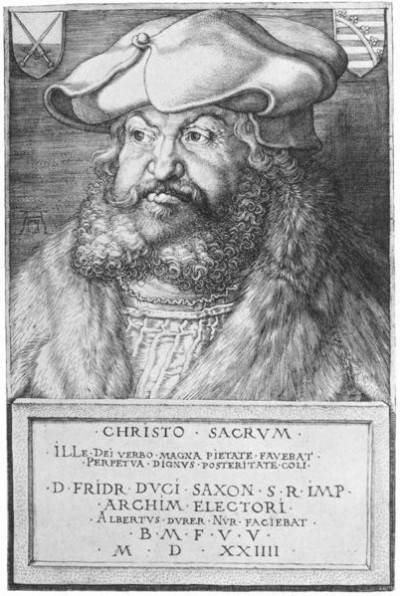

1524 portrait of Frederick III, elector of Saxony

1524 portrait of Frederick III, elector of Saxonyby Albrecht Dürer

Perhaps most significantly of all, the papal bull was sent to Frederick the Wise, who consulted the famous scholar Erasmus and was advised to ignore it as offensive to all upright men.

1520: Address to the German Nobles

On August 18, 1520 four thousand copies of Martin Luther's Address To His Most Serene and Mighty Imperial Majesty, and to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, Respecting a Reformation of the Christian Estate were released. They spread rapidly, and new editions were immediately called for.

On August 18, 1520 four thousand copies of Martin Luther's Address To His Most Serene and Mighty Imperial Majesty, and to the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, Respecting a Reformation of the Christian Estate were released. They spread rapidly, and new editions were immediately called for.

The book is a most stirring appeal to the German nobles, who, through Hutten and Sickingen, had recently offered their armed assistance to Luther. He calls upon them to take the much-needed Reformation of the Church into their own hands; not, indeed, by force of arms, but by legal means, in the fear of God, and in reliance upon his strength. The bishops and clergy refused to do their duty; hence the laity must come to the front of the battle for the purity and liberty of the Church. (ibid., ch. 3, sec. 45)

One of the more interesting parts of the book is Martin Luther's description of the three walls of Jericho, which he intended to pull down. They were:

- The exclusion of the laity from control of the Church

- The exclusive right of the Romish clergy to interpret the Scriptures

- The exclusive right of Rome to call a council

After he attacks all three ideas, he complains about the worldliness and pomp of the pope and cardinals, and then he gives practical suggestions for reform.

The Church, the State, and Nobility

You may note here that the address is to the nobility, not to the people. Luther still had not gained the idea that the Church should be separated from the secular government.

Reform without the secular government may seem impossible, but it is exactly what the apostles accomplished through their churches. It seemed to have taken three centuries, but it did not. The goal was not to obtain a Christian government; the goal was to preach the Gospel to all creation. That task was accomplished in the first century, and Christians increased in number from the time of the apostles onward, with or without the support of the secular government.

In fact, even in Luther's time, the Anabaptists—also known as the Radical Reformation—were carrying on a reform in the manner of the apostles … and succeeding.

Though the Anabaptists could never grow in numbers as fast as the Lutherans, who obtained the required conversion of entire states, they grew and continued to grow until the Baptists—descendants of the Puritans and influenced by Dutch Anabaptists—created a similar free church system in England.

1520: Martin Luther Burns the Papal Bull

Luther then turned his attention to the papal bull.

His response was swift and confident. He wrote a tract called Against the Bull of Antichrist in which he denounced the pope as a heretic. He then publicly announced that he would burn all the writings of the hardened heretic and antichristian suppressor of the Scriptures.

On December 10, 1520, he did exactly that. First he burned the bull itself, and then the papal decretals, a copy of canon law, and several writings of Eck. As he did so, he proclaimed, "As you have vexed the Holy One of the Lord, so may the eternal fire vex you!"

Shortly after, he wrote a public explanation called "Why the Books of the Pope and His Disciples Were Burned by Dr. Martin Luther."

1521: The Diet of Worms

The Diet of Worms requires separate coverage. Due to the trial of Martin Luther, it is one of the most famous events in history. It was there that Luther uttered the following famous words in front of churchmen, the emperor, the Electors of Germany, and virtually every other dignitary of central Europe.

Here I stand! I cannot do otherwise. God help me! Amen.

There are actually some questions about whether he actually said the words, "Here I stand." However, if Martin Luther did not say them, it was most certainly the message he conveyed. He made it clear that he believed the councils were not infallible, and that he could not and would not recant unless he was proven wrong from Scripture.

1521: The Imperial Edict Against Martin Luther

The emperor was basically forced to issue an edict against Luther. He waited until all the electors had left Worms, and then he commissioned Aleander to draw it up.

It's quite strong. It denounces Martin Luther as a devil in the guise of a monk, and it commands the burning of all his works. It put him under imperial ban, thus causing him to lose all protection of law. Finally, it demands his arrest, wherever he might be found.

It did, however, honor the promise of safe passage, giving Martin Luther 3 weeks to return to Wittenberg (and, as it turned out, for Frederick the Wise to seize and hide him).

The power of the German nobles, however, and the popular—and increasing—support of most of Germany, ensured that the imperial edict was not carried out any more than the papal one had been.

1521-22: Junker Georg

Frederick the Wise, "the fox of Saxony," arranged for Martin Luther to be arrested on the way back to Wittenberg. He was captured by cursing soldiers, and he was taken to Wartburg castle, near Eisenach, though almost no one knew of his whereabouts.

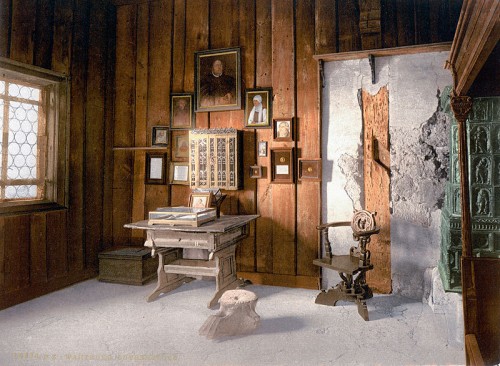

Wartburg Castle around 1900

Wartburg Castle around 1900He took up the name of Junker Georg, and he was held as a noble prisoner there. He put on noble clothes and a sword, and he grew out his hair and beard.

Eleven months he was held there, and during that time he translated the New Testament. He conversed with many people, but he never let them know who he was. He even occasionally discussed his own disappearance with priests and monks. There was much speculation, but most thought he was dead.

Martin Luther's room in the Wartburg Castle

Martin Luther's room in the Wartburg CastleIt was also here that Martin Luther began his many encounters with the devil, whether real or imagined. He heard noises and saw visions, even claiming to have thrown the devil out the window in the form of a black dog that never barked.

Martin Luther had a very real belief in the devil. He once even said that the devil steals children and replaces them with lumps of flesh that torment the parents, then die young. (Denn diese Gewalt hat der Satan, dass er Kinder auswechselt und einem für sein Kind einen Teufel in die Wiegen legt.)

This was a difficult time for Martin Luther. He speaks of his spiritual difficulties in a letter to Philip Melancthon, found in De Wette:

I see myself insensible, hardened, sunk in idleness, alas! seldom in prayer, and not venting one groan over Godís Church. My unsubdued flesh burns me with devouring fire. In short, I … am devoured by the flesh, by luxury, indolence, idleness, somnolence. Is it that God has turned away from me, because you no longer pray for me? You must take my place; you, richer in God's gifts, and more acceptable in his sight. Here, a week has passed away since I put pen to paper, since I have prayed or studied, either vexed by fleshly cares, or by other temptations. (II:21, as found in Schaff, History of the Christian Church, vol. VII, ch. 4, sec. 61)

1522: Martin Luther Puts a Stop to Violence

De Wette, a collection of Luther's letters

De Wette, a collection of Luther's lettersphoto by Delta x

During Luther's captivity, his friends began to reform things on their own. They turned violent rapidly.

Only a month after Martin Luther's imprisonment, two priests were excommunicated in Erfurt for taking part in celebrations after the Diet of Worms. Twelve hundred students and workmen ransacked up to sixty priests' houses in retaliation, and the priests themselves were forced to flee.

Disorder and unrest continued as Martin Luther was forced to remained holed up in Wartburg.

Finally, Luther could bear it no longer, and he returned to Wittenberg at great danger to himself in March of 1522. Immediately, he preached eight sermons in eight days, quenching the violence and setting a course for the Reformation.

One point is important, for Luther is accused of promulgating violence and promoting the physical persecution of heretics. He preached:

I will preach, speak, write, but I will force no one; for faith must be voluntary. Take me as an example. I stood up against the Pope, indulgences, and all papists, but without violence or uproar. I only urged, preached, and declared God's Word, nothing else. … Had I appealed to force, all Germany might have been deluged with blood; yea, I might have kindled a conflict at Worms, so that the Emperor would not have been safe. But what would have been the result? Ruin and desolation of body and soul. …

Do you know what the Devil thinks when he sees men use violence to propagate the gospel? He sits with folded arms behind the fire of hell, and says with malignant looks and frightful grin: "Ah, how wise these madmen are to play my game! Let them go on; I shall reap the benefit. I delight in it." But when he sees the Word running and contending alone on the battle-field, then he shudders and shakes for fear. The Word is almighty, and takes captive the hearts. (ibid., ch. 4, sec. 68)

1525: The Peasants War

Martin Luther Encourages Mass Violence

Martin Luther's handling of the peasants' revolt can be justified as an idea or as a doctrine. All authority, according to Romans 13:1, is ordained by God, and revolution against the government will be met by violence.

On a conscience level, however, nothing about Martin Luther's handling of the peasants' revolution can be justified. Perhaps because of his intense opposition to Thomas Münzer, or perhaps for some other reason, he took an extremely violent stand on behalf of the nobility. Martin Luther had been a peasant himself, and he sympathized with their complaints, but his wording concerning the Peasants War of 1525 is simply unconscionable.

He wrote a tract entitled Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants. In it he accuses the peasants of being the worst blasphemers of God because they used the Gospel to justify their rebellion. He wrote, "I think there is not a devil left in hell; they have all gone into the peasants."

His lack of toleration for the revolt was one thing, and probably justified. His call to action was quite another:

Therefore let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel.

Luther called for the peasants to be put down like mad dogs, and the nobility complied. It is possible that 100,000 peasants were killed by the nobles and their armies, and it didn't take them long to completely quench the rebellion.

Many citizens, disappointed, turned from promoting the Reformation at that time. Martin Luther suffered great harm to his reputation, and the Roman Catholics seized the opportunity to blame him (accurately?) for the deaths.

1525: Luther Marries Katharina von Bora

Mrs. Martin Luther, Katharina von Bora

Mrs. Martin Luther, Katharina von BoraOddly enough, it was right at the end of the Peasants War, on June 13 of 1525, that Luther decided to marry.

There were obvious reasons for it. The Roman Catholic Church required celibacy of its clergy, and this practice was clearly unscriptural (1 Tim. 3:2). Marrying would set an example that Martin Luther was leading by Scripture and not by Catholic tradition, nor by his monasterial vows.

He married Katharina von Bora, a nun that he had helped escape from the convent. He had helped her get engaged in 1523, but her fiancé broke her heart by marrying a rich woman. Luther then tried to espouse her to a friend, but she refused. Finally, he took her as wife himself.

Interestingly, Martin Luther had six children, though they are rarely mentioned. Two of his three daughters died young, not unusual in medieval times, but the rest all lived into adulthood. One became a physician of the Elector; none of the others were notable.

Some Personal Notes About Martin Luther

Martin Luther was a committed to the faith, though he obviously had a temper problem. The accusations of habitual drunkenness, very popular in the home church movement because of the poor history promulgated by Gene Edwards and Frank Viola, have no validity.

In 1530, a companion, Veit Dietrich, wrote of him:

No day passes that he does not give three hours to prayer, and those the fittest for study. Once I happened to hear him praying. Good God! how great a spirit, how great a faith, was in his very words! … My mind burned within me with a singular emotion when he spoke in so friendly a manner, so weightily, so reverently, to God. (ibid., ch. 5, sec. 78)

Martin Luther and Anti-Semitism

Luther was apparently not anti-semitic as a younger man. In 1516 he wrote that people who condemn the Jews need to remember their own guilt before God. In 1523 he wrote that it was important to be kind to Jews for the sake of evangelism.

Two decades later, however, he raged against them in About the Jews and Their Lies. He recommended setting their synagogues on fire and destroying their prayer books. He recommended destroying their homes so that they would be expelled for all times.

Like the tract against the peasants' rebellion, there is no justifying this sort of language or hatred.

Martin Luther in Old Age

Obviously Martin Luther had some problems as an aged man. No one can say the sort of things he said about the Jews unless something is desperately wrong with their thinking.

It is just as obvious that Luther was not so given to promoting violence as a young man. Perhaps the Peasants rebellion changed him. More likely the stress of his life, including numerous health problems, drove him crazy.

Luther had Meniere's Disease, which produces vertigo and tinnitus (dizziness and ringing in the ears). He had problems with an ulcer or bad digestive problems as a younger man. The last ten years of his life, he had kidney stones and arthritis.

Perhaps it's no surprise that he reached the state he did in his later years.

Martin Luther and Scatalogical Comments

Luther is famed for his comments about the toilet, feces, the devil, and private parts. Many of the quotes attributed to him are difficult to track down. William Manchester, in his book A World Lit Only by Fire, lists a number of them and gives references. [Beware! His section on the medieval popes should be rated NC-17]

He is said once to have proclaimed, "I routed the devil with a fart."

I cannot produce all the references, but there is no doubt he was prone to such languages. His booklet against the Jews, written in 1543, says the following of those who would follow the Jews:

Let him tell the Jews to use his mouth as a privy, or else crawl into the Jew's hind parts, and there worship the holy thing.

Some of my friends and I have wondered if Martin Luther was schizophrenic.

Martin Luther and Theology

I believe the Reformation to have been far more a political change than a theological one. Luther's break with Rome had far more to do with his views of their authority than with any particular doctrine.

Johann von Staupitz, Martin Luther's mentor

Johann von Staupitz, Martin Luther's mentorAs noted above, a papal bull was issued in 1520 condemning him on 41 points from his books. Not one of those mentions salvation by faith alone, which most people consider to be the primary reason he split with Rome. It was not, and the faith he preached was not completely new. His superior while he was a monk, Johann Staupitz, taught him much of the reliance on faith that was central to his later theology, and Staupitz went through no separation from Rome.

In fact, it was not only Staupitz. An unnamed monk helped him get over the berating of his own conscience while he was still in the monastery, before he ever began preaching, even for Rome:

In this state of mental and moral agony, Luther was comforted by an old monk of the convent (the teacher of the novices) who reminded him of the article on the forgiveness of sins in the Apostles' Creed, of Paul's word that the sinner is justified by grace through faith, and of an incidental remark of St. Bernard (in a Sermon on the Canticles) to the same effect. (Schaff, ibid., ch. 2, sec. 22)

Luther's views on predestination in his book The Bondage of the Will, were also not new. They were not dissimilar to Calvin's, and he got them from studying St. Augustine. Again, this did not separate him from Rome any more than it would have separated Augustine from Rome, had there been a pope in Augustine's day.

The Reformation doctrine of sola Scriptura did lead to the separation from Rome. Martin Luther did argue that even the pope and councils must be subject to Scripture. As I pointed out, however, this doctrinal matter concerned authority. It was no particular doctrine of Scripture, but a battle over indulgences, that led to the conflict between Scripture, pope, and councils for Martin Luther.

Early Church History Newsletter

You will be notified of new articles, and I send teachings based on the pre-Nicene fathers intermittently.

When you sign up for my newsletter, your email address will not be shared. We will only use it to send you the newsletter.